The story of Brandy Hole Copse

(This webpage was published on 6th September 2024 and all content added by 31st October 2024.)

The following is a transcript of the publication by the Brandy Hole Copse Conservation Group (forerunner of the Friends of Brandy Hole Copse). Images are photographs made of that publication.

The original is available to read at/from Chichester Library, which holds 2 lending copies and a reference copy:

Chichester's Green Secret, Story of Brandy Hole Copse

Author: Brandy Hole Copse Conservation Group

Year: 2001

Media class: Paperback

Classification: 639.95CHICHESTER, 914.225

Publisher: Brandy Hole Copse Conservation Group

Resource type: Physical

Pamphlet

ISBN: XX00030711

Use the following links to jump to the relevant sections of the publication:

- Introduction

- A place we should cherish

- Iron age entrenchments (From Iron Age to the new millenium)

- The Broyle (From Iron Age to the new millenium)

- Smuggling (From Iron Age to the new millenium)

- The twentieth century (From Iron Age to the new millenium)

- Overview by West Sussex County Council's Senior Ecologist

- Photos & Map

- Geology and geomorphology (A place of variety and interest)

- Soils and climate (A place of variety and interest)

- Birds (A place of variety and interest)

- Mammals (A place of variety and interest)

- Bats (A place of variety and interest)

- Moths and other insects (A place of variety and interest)

- Ponds (A place of variety and interest)

- Flowering plants and the copses (A place of variety and interest)

- Bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) and lichens (A place of variety and interest)

- Trees (A place of variety and interest)

- A general view of the woodland (A place of variety and interest)

- Managing the Copse: the past and the future

- Thank You, Everyone

- 2002 update

- Back cover

Inside front cover

“All the year round Brandy Hole Copse is a great place to walk with the grandchildren and the dogs.” “The copse beside Brandy hole lane is not only green and tranquil, it is also steeped in the romance of its ancient history.” “Your copse is a unique blend of ancient woodland, coppiced glades, and picturesque ponds. We love it!”

These are the sort of comments which are made by local people about Brandy Hole Copse. But most Cicestrians are only vaguely aware of this very special place, the largest accessible woodland on their doorstep.

This booklet, with its descriptions of the Copse past and present, will, we hope, remedy this. But it has also been produced to celebrate a brighter future for Brandy Hole Copse as it enters a new phase in its long history. It has been identified as a key site in Chichester District Council's Local Biodiversity Action Plan and will soon be designated as a Local Nature Reserve - a move which will bring more resources and support for its conservation.

To find out more about the Copse, read on...

John Herniman, Chairman

Brandy Hole Copse Conservation Group

May 2001

CONTENTS:

Introduction page 1

The past – digging, hunting, smuggling page 3

The present – the flora and fauna page 17

The future – the Copse in the 21st century page 23

Back to List.

A place we should cherish

Brandy Hole Copse is some 15 acres of mostly coppiced woodland, lying along the south side of Brandy Hole Lane, on the north-western outskirts of Chichester. Part of it belongs to the Chichester District Council, and the remainder to two local private landowners.

Through it runs part of the Chichester Entrenchments, a massive bank and ditch system thought to date from the late Iron Age and now a scheduled ancient monument. More modern history is represented by the old Chichester to Midhurst railway line, now the Centurion Way cycle and foot path, which cuts through the eastern end of the Copse.

The current Copse is of comparatively recent origin, though some 10,000 years ago it formed part of the extensive woodland covering the Sussex coastal plain. It is regarded by ecologists as an old secondary wood of high biological interest. As old secondary woods are even rarer than ancient woods, this reinforces the importance of the Copse’s survival on conservation as well as a recreational grounds. It is identified as a priority wildlife site under the Chichester District Council Local Biodiversity Action Plan.

A management plan for next five years aims to maintain the Copse as an informal woodland area, conserve the diversity of flora and fauna, protect the archaeological remains from further damage, enhance the area's value as an educational resource for local residents and schools, and increase community involvement. An essential part of this will be the installation of at least three information boards, to tell the story of Brandy Hole Copse. The Copse is also to be designated a Local Nature Reserve during 2001, which will increase the protection available and also open up gateways to extra grant aid.

The awakening of public interest in the Copse dates back to the great storm in October 1987 when many of the mature oaks and other trees were blown down, causing extensive damage, particularly to the entrenchment bank. Chichester District Council removed most of the fallen trees and then asked for public support to form a local group to look after this area of woodland.

A public meeting called by Sussex Wildlife Trust and CDC in August 1989 resulted in the formation of the Brandy Hole Copse Conservation Group, which has managed the Copse on a voluntary basis ever since. Many individuals have made very substantial contributions throughout the 12 years of the Group's existence, but it is team effort which has achieved so much.

With advice from SWT, the British Trust for Conservation Volunteers and West Sussex County Council, and financial help from Chichester District Council, a small working party started in 1990 to clear the undergrowth, plant some 1500 trees and bushes, and re-establish the hedge along the roadside. The first major task was to erect a post-and-rail chestnut fence along approximately 300 yards of the road boundary and replant the hedge, which was done with the help of soldiers from the nearby RMP barracks.

Initially the Conservation Group dug out two wetland areas to form ponds - Willow Pond and Cops Pond, the latter named in recognition of the RMP's contribution - and dredged the silted up Brandy Hole Pond. Other work has included clearing many pathways and laying new ones, building stiles and steps to improve access, putting up owl and bat boxes, and installing information boards. Surveys of bird and insect populations have been undertaken, and general conservation work continues. The Group supported the creation of a permanent public right of way running between Bristol Gardens and Brandy Hole Lane, which is likely to be adopted and upgraded by WSCC as part of a formal access to Centurion Way. More recently, Brandy Hole Pond has been re-dredged and enlarged, work generously funded by Portsmouth Water plc, and the pond paths raised above winter flood levels.

The Conservation Group is most grateful for past help from the RMP and the Crumblies hedge-laying team which worked on the western boundary of the Copse, for generous donations from individuals and for continuing support from the British Trust for Conservation Volunteers and Youth Outset Action students from Bishop Luffa School. However, most of the work is done by a small and dedicated band of volunteers, who will always welcome more help.

The Copse is open to the public at all times. It can be reached from entrances at either end in Brandy Hole Lane, as well as from Bristol Gardens and Centurion Way. There is pedestrian access only (limited roadside parking is available at the western end) and cycling is not permitted west of Centurion Way (cycle racks are provided on the Centurion Way and at the western entrance).

Back to List.

From Iron Age to the new millenium

The archaeology and history of the Copse,

by John Mills, County Archaeologist

Iron age entrenchments

In 1797 William Sabatier and an unnamed local rector walked the countryside around Chichester over a period of five weeks, noting a remarkable series of straight linear earthworks which he described as “Roman military works”. Over a century earlier (c. 1670), the famous antiquary John Aubrey had noted on the north side of Chichester “Neer to Chichester westwards is an extraordinary Roman Campe oblong, called the Broyle or Brile... This is in flatt low ground with a great rampire (rampart) and single graffe (ditch)”. Lieutenant William Roy, in his map of Sussex, finished in February 1757, also noted “A Roman Camp” and long, straight earthworks here.

One of these linear earthworks runs westwards for two kilometres from the present Summersdale Road, along the Broadway, Brandy Hole Lane and Old Broyle Road. It is visible today in Brandy Hole Copse as a substantial bank with a ditch on its north side. Towards the eastern edge of the Copse, another, shorter, stretch of bank and ditch runs from south to north, to meet it at right angles. On a sketch of Aubrey's, the south-north earthwork is marked as in or adjoining “copicewood” (see below).

Aubrey interpreted some of the earthworks near Chichester as three sides of a rectangular fortification: north-south earthworks in Brandy Hole Copse and parallel to Summersdale Road, with the Brandy Hole Lane-Broadway earthwork linking them. These earthworks, however, form part of a larger complex. The system, the Chichester Entrenchments, extends, in discontinuous lengths, from East Ashling and West Stoke in the west to Halnaker in the east (though another group of probably related earthworks occurs as far east as Rewell Wood and Binsted). Aubrey, Roy and Sabatier believed them to be Roman in date, Aubrey thinking they dated to the time of the Roman conquest of Britain (43 AD): “Quare (query) where Vespasian landed. Julius Caesar's memoires did lett them know how he was impeded by the River Thamesis wherefore they might thinke good to land more westward, perhaps in Sussex as did Wm. Ye Conqueror.”

In fact, where the earthworks (known as the Devil’s Ditches) can be dated, they appear to have been constructed in the Late Iron Age, probably the period between 100 BC and the Roman invasion (43 AD). Groups of Late Iron Age earthworks, known as “territorial oppida” (in Latin, “fortified towns”, but often used today to describe Late Iron Age tribal capitals with circuits of earthwork fortifications) have also been recorded around Colchester and St Albans, both certainly Late Iron Age tribal capitals. The long linear earthworks may have been intended to define, and if necessary defend from attack (eg. by neighbouring tribes), in this case not a town but a territory. This territory would have been a core settlement area of the coastal plain around Chichester and Fishborne, agriculturally productive land with two harbours (Chichester and Pagham).

In Late Iron Age times the entrenchments would have been even more substantial than today's banks and ditches, as the banks will have eroded somewhat and the ditches have probably silted up over the years with several feet of gravel and topsoil. The banks, six to nine metres wide, still stand up to three metres high in places, with the ditch 6 metres wide. They must once have presented a formidable obstacle, and certainly were a formidable undertaking for the people who built them - one estimate is that their construction took a million and a half man hours.

Back to List.

The Broyle

In the eighteenth century, Brandy Hole copse (properly, East Broyle Copse) lay at the eastern edge of the Old Broyle Common. The place-name Broyle preserves a common medieval term for enclosed park or woodland stocked with deer and other beasts of the chase. During the reign of Henry III it was a royal hunting ground, documented as Brullius Regis, the “King’s Broyle”. Later in the thirteenth century it is referred to as boscus de Bruyll, the “Broyle wood”. Documentary references and later “Broyle” place-names suggest that the Broyle extended at least from Graylingwell and the Midhurst Road on the east to Oldwick Farm on the west.

Some of the Entrenchments, apparently running north-south and east-west, immediately north of Chichester, are mentioned in a document of 1225, and defined different holdings of woodland in this area. The Entrenchments in Brandy Hole Copse may well have been re-used in medieval times as woodland and medieval park boundary banks within the hunting forest of the Broyle. Indeed, to the north-east and north-west of Chichester, some linear earthworks seem to have been added to existing ones in the Middle Ages, perhaps to complete game park boundary circuits.

By 1757, when the earliest detailed maps of the area to the north of Chichester survive, it can be seen that a number of roads and a stream ran through the Broyle. The stream may have risen in the area of Warren Farm, but certainly flowed southwards through the Brandy Hole pool, east of and parallel to the modern railway line. The meadows through which the stream ran were known in the nineteenth century as The Slab, no doubt connected with a Sussex dialect word “slabby”, meaning “dirty, wet, slippery, greasy, sticky”.

In 1771 (William Gardner's Plan of the Manor of Broile) the modern fields on both sides of the “Slab stream”, extending from the eastern edge of modern Brandy Hole Copse to the Broyle Road, were coppiced woodland. The strip of land on the South side of present-day Brandy Hole Lane, now a gravel pit, was recorded as part of The Common, ie, waste land. The stream seems to have divided the ancient Broyle into two areas, The Broyle or New Broyle to the east, and the old Broyle to the west. The coppice east of the stream was called The Broyle Coppice, that to the west The Old Broyle Coppice.

In the 18th century Brandy Hole Copse was part of the large area of common and waste known as the Old Broyle. Yeakell and Gardner’s map of 1778-1783 and a Plan of the Manor of East Lavant, dated 1791, clearly show the distinction between the Old Broile Coppice to the east and Brandy Hole Copse to the west, which was rough common land only. So at this date there was apparently no managed woodland in Brandy Hole Copse. However, the “copicewood” noted by Aubrey, in his sketch map of c.1670, may imply that at an earlier date at least some of Brandy Hole Copse was included within the larger Old Broile Coppice.

Also clearly marked by Gardner in 1771, and by later mapmakers, is a large “Gravel Pit” in the north-western part of Brandy Hole Copse. The pitted nature of the ground in this area, and the modern Cops and Willow Ponds, owe their existence to the ancient gravel digging here, most probably for material for road building and maintenance from the Middle Ages onwards.

At some time between 1825 and 1846, the Old Broile Coppice was cleared and ploughed. In 1840 Brandy hole copse was “rough” common, probably used for grazing of livestock. The strip of land west of the Brandy Hole pool - the “Brandy Hole strip” - was recorded as “gravel pits and common waste”; in 1841 there may have been new gravel digging going on next to Brandy Hole Lane. It must have been at this period that almost the whole of the surviving Iron Age entrenchment in the Brandy Hole strip was destroyed by gravel digging. In 1875 (first edition Ordnance Survey map) Brandy Hole Copse, and the lane further west, is shown for the first time as wooden plantation, mixed deciduous and coniferous woodland. Evidently trees had been planted on the former common land, probably not long after 1840.

Back to List.

Smuggling

The Brandy Hole pool itself, a name redolent of Sussex smugglers, is at least eighteenth century in origin, most probably much earlier, a natural spring-fed pool. It is clearly marked on William Gardner's map of 1771, but did not appear on every map thereafter - it may have been dry at some periods. The name “The Brandy Hole” is first known now from the 1875 Ordnance Survey map, before the railway was built. Smugglers had been hanged and put on a gibbet on the Broyle in the mid-eighteenth century (the site of the gibbet lay in the centre of the modern Rousillon Barracks).

However the smuggling connections of this area are more tangible. At the end of March 1841 the following was reported: “A cave was discovered in a gravel pit on the Old Broyle. The subterranean excavation has been traced 158 feet, the whole of which is cut under the gravel in the true arch, the circle of which is correctly made throughout. It is thought to be about 150 years old, as the fragments of bottles, the bottoms especially, are of the shape and colour of wine bottles of that day. That it was a secret place for concealing smuggler’s goods, there is no doubt, for formerly there was a thick copse of trees.” (19th-century notebook on: Remarkable Events in the City of Chichester, West Sussex Records Office ADMS 29710)

The description best fits the Brandy Hole strip, formerly at the edge of the Old Broyle Coppice, at that time recently felled and cleared. Moreover on the 1896 Ordnance Survey map, marked within the “old gravel pit” in the Brandy Hole strip or three “entrances” to the “Smugglers’ Cave”, right next to the Lane: could the 1841 tunnel have been dug under the Lane? “Roman Caves” also marked on the 1896 map on the eastern edge of the Copse are almost certainly geological swallow holes! Both caves also appear on the 1912 OS map.

Earlier this century, the entrance to the caves was thought to be nearer the London Brighton & South Coast branch railway line from Chichester to Midhurst, built in 1880-1881, and closed to regular passenger traffic in 1935 (freight traffic, mainly sugar beet, continued to run until 1970, and a “gravel train” until the line was formally closed in March 1991): “The cave from which Brandy Hole Lane, Chichester, obtains its name is, or was, in the lane close to the Midhurst railway line. The entrance to it until the railway line was built, was open, I believe it was filled in during the building of the road bridge; It was an apartment of considerable size, with a passageway leading north.” (Changing Chichester, by Bernard Price, 1982, Pl. 3, Phillimore)

In the later nineteenth century a brandy barrel, one of a number that had been discovered in caves in Brandy Hole Lane, hung in the window of Benham’s dining room and beershop at 75 North Street for many years. There was also once a “smuggler’s sword”, found in the Old Boyle, in the collections of the former Chichester Guildhall Museum. More recently, in the 1960s, a subterranean brick- built chamber, with arches in the walls, was discovered during electricity board works near the present substation. Could there be a smuggling connection here?

Despite the confusion about the location of the entrances to the “smuggler’s caves” (there may have been several caves), the documentary references could all refer to the initial discovery of 1841. Perhaps other cave entrances were found after 1841, but not noted. Also interestingly, the cave entrances led northwards. Could they all originally have been dug into the side of the Iron Age entrenchment ditch?

Back to List.

The twentieth century

Nothing came of a World War One plan to build a halt on the railway line at Brandy Hole Lane to serve the barracks, then home of the Royal Sussex Regiment. But still visible in the bottom and along the top of the bank of the Brandy Hole strip are a number of 5ft concrete cubes and “dragons’ teeth”, which were originally built as World War Two anti-tank defences, part of the country’s protection effort against potential German invasion.

The most recent event in the history of the Copse and its environs is the creation of the Centurion Way, a cycle path along the disused Chichester to Midhurst railway line which cuts through the Copse. This was opened in September 1995. Earlier history is marked, though, in the metal figure over the mounted Roman centurion set at the exit from the cycle path towards Brandy Hole Lane.

Back to List.

In Brandy Hole Copse you can see examples of our native trees and shrubs, and in addition examples of species which have been introduced by humans - the sweet chestnut and sycamore of the most obvious. Bluebells grow under the trees, butterflies flutter through, frogs are found in the ponds and dragon flies hover above them, familiar woodland birds can be seen or heard.

If you had been standing in the Copse say 10,000 years ago it is likely that it would have been part of a much more extensive forest covering the coastal plain. There would have been no Chichester and indeed no permanent settlements at all. But there would have been oaks, hazel, field maple, hawthorn.

Some 8,000 years later, just before the Romans arrived, the entrenchments which run through the Copse were most probably newly built, and bare of the large trees which now dominate them.

Where once prehistoric people gathered nuts and fruit, and wild boar rooted for acorns, walkers now exercise their dogs. The oaks which now tower over the coppiced chestnut may be 150 years old or more - when they were very young Queen Victoria was on the throne and the Crimean war was about to start.

This modern Copse is very different from the Wild Wood of 10,000 years ago, but it is a fascinating asset, open to all to enjoy and to help to preserve.

Ann Griffiths,

Senior Ecologist,

West Sussex County Council

Back to List.

[Photos below from page 9 - photos of the the print copy, so may be slightly distorted/cropped compared to the originals. Layout described is not reproduced here.]

At work in the Copse:

Top, dredging of Brandy Hole Pond in November 2000, a project paid for by Portsmouth Water.

Right, young soldiers from the RMP barracks clearing a path in 1993.

Below right: Cops Pond under construction in 1991.

[Photos below from page 10 - photos of the the print copy, so may be slightly distorted/cropped compared to the originals. Layout described is not reproduced here.]

Brandy Hole Copse history:

Left, mature beech trees growing on the entrenchment bank.

Above, World War II “dragons teeth” anti-tank defences in the Copse.

Below, more anti-tank defences behind volunteers working in the entrenchment ditch.

[Photos below from page 11 - photos of the the print copy, so may be slightly distorted/cropped compared to the originals. Layout described is not reproduced here.]

Top, fence building 1990; above right, ready for work 1993; above, snow 1996; right, smiles after the 2000 pond dredging.

[Map below from the centre spread, pages 12/13, is a photo of the the print copy, it is slightly distorted compared to the original.]

Brandy Hole Copse:

The Copse past and present, from a 1912 Ordnance Survey map updated to include later 20th century features.

Original map held by West Sussex County Council Record Office

[Photo of page 14 - may be slightly distorted/cropped compared to the original.]

Broad buckler fern, above, is found in several locations in the Copse.

Left, the speckled wood is the commonest butterfly, while the elephant hawkmoth (below) and stag beetle (below left) are much rarer residents.

Photos here and opposite: Mike Perry

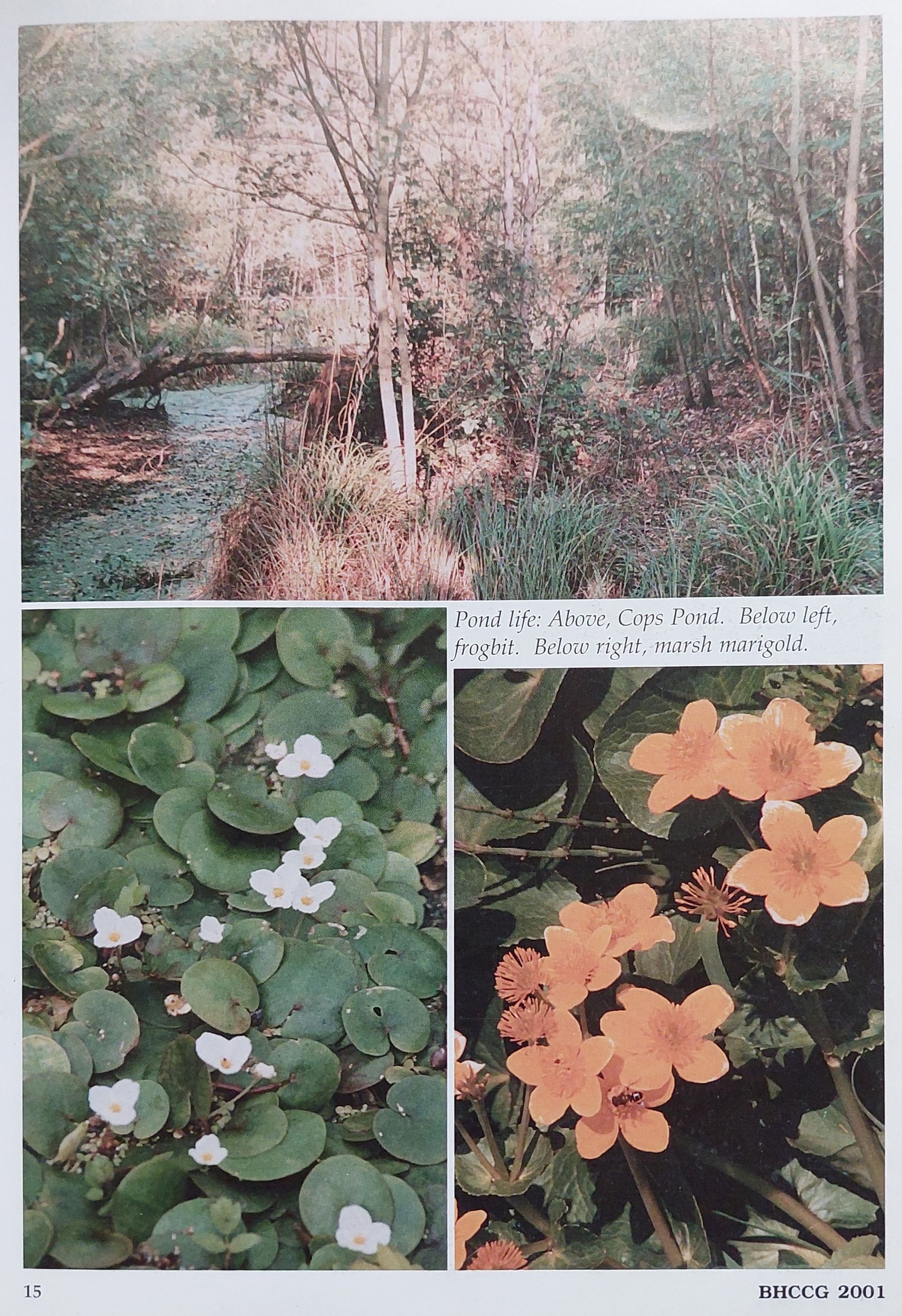

[Photo of page 15 - may be slightly distorted/cropped compared to the original. Original photos by Mike Perry.]

Pond life: Above, Cops Pond. Below left, frogbit. Below right, marsh marigold.

[Photos below from page 16 - photos of the the print copy, so may be slightly distorted/cropped compared to the originals. Layout described is not reproduced here.]

Coppiced sweet chestnut, left, dominates the woodland of the Copse.

Below, Willow Pond.

Photos: Mike Perry

Back to List.

A place of variety and interest

The flora and fauna of the Copse,

By members of Chichester Natural History Society

Detailed information on the flora and fauna of the Copse is now available, thanks to Chichester Natural History Society. In 1999 CNHS members, in co-operation with Brandy Hole Copse Conservation Group and West Sussex County Council, began a recording project at the Copse, contributing expertise, enthusiasm, time and knowledge to the task. In all cases the sampling was carried out in May and June, so for seasonal flora and fauna the picture is limited to that period of the year.

The findings and recommendations, recorded in detail in a report published by the CNHS in October 2000, are a major contribution to the future management of the Copse. The surveys have shown the site to be of a varied character, reflecting its past and present use and management. Some of the topics covered in the report are summarised here.

WHY IS THE COPSE LIKE IT IS?

Geology and geomorphology, by Mike Goodchild

The geology of the site has to be set in context to the rest of the “high level” West Sussex coastal plain. Locally the site is similar to ground under the Barracks, the area of Summersdale north of the Broadway, as well as north of Brandy Hole Lane and, in part, to the fields of Raughmere Farm and the worked-out gravel pits of Hunter’s Race.

The solid geology is simple. Chalk was deposited during the late Cretaceous (100 million years Before Present). There followed a period of slight uplift and erosion followed by the deposition of a complex sequence of Tertiary beds (65 million years BP), of which only the lowest one, the Reading beds, concerns us. Next, there was a prolonged period of uplift and erosion during the Miocene (26 million years BP) when the structure of the Weald anticline was formed and then eroded to roughly its present topography. The Pleistocene (2 million years BP) period followed with its sequence of glacial and interglacial episodes with falling and rising sea levels. The complex sequence of drift deposits, sands, gravels and clayey gravels were then deposited to form the gravel beds that were worked, over time, at the site.

During the Cromer interglacial period (the second of four interglacials within the Pleistocene) there were high sea levels. The sea encroached across the gently dipping Tertiary and chalk strata creating an eroded plain, often called a “raised beach”. This was much further inland than today's coastline, roughly east-west from Aldsworth to Arundel. Marine sands were deposited on this surface but are now only preserved in patches. Whether any such material lies at the base of the Brandy Hole Copse gravels is unknown. Subsequent glacial episodes transported much clayey gravel material across this platform.

At least three such episodes were separated by warm interglacial conditions (similar to or slightly warmer than the climate today). Downcutting by streams in the cold spells dissected this high-level platform into patches, interrupted by the valleys of present-day streams e.g. the Ems and the River Lavant. The gravels of Brandy Hole Copse were then decalcified by interglacial weathering and thoroughly mixed by periglacial movement. The last phase of the final glacial episode (Devensian 12,000- 14,000 BP) saw the deposition of a thin layer of wind-blown dust (loess) on the landscape surface. This, too, survives only in patches and at Brandy Hole Copse it has been washed into the top of the gravels making them clayier. During the postglacial period (since 10,000 BP) the weathering and decalcification has continued.

A feature of the Brandy Hole Copse area is the presence of swallow holes. There is always much lateral and vertical water movement within the chalk, generally within fissures and joints. Water can flow south under the Reading Bed clays before flowing vertically down a favoured route, thus enlarging the fissure. This process can also happen under the impervious clayey gravels. Eventually the load becomes too great for the bridging material to sustain and as the cavity beneath grows wider a catastrophic collapse takes place and a hole appears. Much smaller circular depressions in the Copse are attributed to swallow holes deep below in the chalk.

Back to List.

Soils and climate, by Brian Hopkins

The Brandy Hole Copse soils are Brown Earths, one of the commonest of the major soil types in Britain. More precisely, they belong to the Charity Series of the Argillic (clayey) Brown Earths, which form a band of drift deposits up to 3 km wide, from Havant to Arundel and overlying the gentle lower dip slopes of the chalk. The Copse soils are an extremely flinty sub-type of this series. They are deep, brown, flinty, clayey, non-calcareous silty drifts.

Brown Earths are deep, nutrient rich, have a thick surface layer of litter, a pH of only about 6 (only slightly acidic) and support large populations of soil invertebrates and micro-organisms. The flinty types, as in Brandy Hole Copse, are particularly well drained and have little surface run-off except where they have been heavily compacted by human activity.

The prevailing south-westerly wind ensures that the local climate is mild and moist. Average temperatures are of little ecological relevance; what is important is the general range and, to some extent, the extremes. July is the warmest month, when the mean maximum temperature is about 20°C, while January is the coldest, mean minimum of about 1°C. Air frosts occur on about 45 nights a year, while ground frosts happen almost twice as often. Snow is infrequent. The mean annual rainfall is about 750 millimetres. Though it is fairly evenly spread throughout the year, the months of November to January are wetter than average, those of April to June drier.

These are climatic conditions that prevail in the more open areas such as East Broyle Copse. Within the steep-sided raving of the earthwork the climate will be very different. Along the bottom it will be generally more shaded and more humid than outside. It will also tend to have a more even temperature - cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter - although it is probably a minor frost hollow in still, frosty weather.

As the ravine runs east-west, the north-facing slope is in shade for much of the time and, consequently, will be cooler and damper than the south-facing slope. No measurements have been made here, but the temperature differences are likely to be several degrees and, ecologically, these micro climatic differences will profoundly affect the distribution of the plants and animals.

Back to List.

WHAT LIVES AND GROWS IN THE COPSE?

Birds, by John Herring and Nigel Moir

During the early summer survey, 16 bird species were recorded. These were common woodland species such as blackbird, blue tit, wren and wood pigeon, with two species of woodpecker, greater spotted and green, present. There were also two summer migrants, blackcap and chiffchaff. This survey did not confirm any breeding species - there was some disturbance from cyclists observed, which may have discouraged the birds. A further survey late in 2000 noted four species from the crow family - rook, crow, jackdaw and magpie, with nests of the first seen. Sparrow hawk, kestrel and hobby falcon were also recorded at that time, as were mallard on the pond.

Mammals

During the Chichester Natural History Society’s survey a number of species of rodents were noted, including wood mouse and house mouse, common rat, voles and shrews. Grey squirrels, rabbits and foxes are reported, and very occasionally dear. Further work is planned to study the population of mammals in the Copse in greater detail.

Bats, by Martin Love

The Copse area has considerable potential for supporting and attracting bats of several species. The range of habitat offers a wide variety of potential roost sites, feeding opportunities and navigation routes to and from feeding grounds. Key features are:

· Open water at several points provides ideal feeding grounds for species such as pipistrelle, Daubenton's, Natterer’s and whiskered bats.

· Wooded areas provide feeding and potential roost sites for these species and also for serotine and noctule bats.

· Open fields (adjacent to the site) are important when unimproved, as in this case, for serotine and noctule bats.

There are reported to be roosts in a house to the north of the site, and there may well be more in the adjacent housing to the south-east. These risks will rely on the Brandy Hole Copse area for food and routes to other feeding areas. It is quite likely that there is a whiskered bat roost in the old railway bridge over Centurion Way.

Moths and other insects, by Mike Perry

A complete picture of the moth populations in Brandy Hole Copse could be obtained only by a programme of regular trapping over a prolonged period. Moths, like many butterflies, tend to favour wood edges where they adjoin open spaces, as such open areas tend to contain a wider range of plants and hence nectar sources. Accordingly, these were the areas trapped. No attempt was made to search for larvae, which would be needed to demonstrate breeding. Many adult moths are highly mobile and, although present, may not breed in the area.

Of the moths identified, the most striking is the elephant hawk moth, which feeds on the nectar of honeysuckle. The others are all relatively common species. However, the understory of privet in the central stretch of the entrenchment suggests the privet hawk, Britain's largest resident moth, and one declining nationally, might occur. Of the butterflies, the commonest was, not surprisingly, the speckled wood, a species which favours paths, rides and light woodland where there is dappled shade.

No systematic search was made for other insect species, although note was made of all those encountered. These did include two species worthy of special note. First, the stag beetle is present. This is Britain's largest beetle, and an endangered species. Its larva lives in rotting wood. Second, hornets were seen in late summer, and these are also declining nationally.

Ponds, by Elizabeth Sturt

The surveys aimed to estimate the species diversity in each pond and assess the ecological “health” of the habitats. Willow Pond showed the greatest species diversity, suggesting that it is in better condition - probably because it is not overshadowed. Brandy Hole and Cops Ponds had lower species diversity, especially Brandy Hole Pond which contains some species associated with oxygen deficiency. Measurement of the pH of Cops and Willow Ponds yielded a surprisingly low reading of 5.5 (i.e. more acidic than expected), which could be due to the natural pH of the ground water or the result of acid rain.

Larvae of frog and smooth newt were recorded, as were four species of damselflies and hawker and emperor dragonfly, with larvae of the hawker abundant in Willow Pond. Among frequent other insects, seen in larva or adult form and principally at Willow Pond, were mayfly, waterboatmen, water flea, water shrimp, water louse and saucer bug. Commonest of the nine molluscs identified was the great ramshorn snail.

Common marginal plants in Willow Pond were sedges (including pendulous, common yellow, remote and hairy), water mint, yellow flag, soft rush and bullrush; frequently-occurring submerged or floating pond plants included Canadian and curled pondweed, watermoss, frogbit, common duckweed (which is the dominant species in Brandy Hole Pond), water milfoil, water soldier, water crowfoot and fringed waterlily.

Flowering plants and the copses, by Nick and Elizabeth Sturt

A number of species recorded in the Copse of associated with ancient woodland, although probably not in a sufficient quantity to prove a long continuity of woodland. Disturbed areas yielded a fair array of opportunist annual “weeds”, while garden species have colonised as a result of the proximity to habitation; there is reason to believe that some non-native shrub species were deliberate plantings. The site has the potential to generate a pleasingly long list of vascular plant species, providing a small but extremely valuable area of good biodiversity. Abundant flowering plants recorded included native bluebell, herb robert, would avens, hawkweed species, wood sage, creeping buttercup, wood dock, nettle. Wavy hair grass is the only abundant grass noted, while bracken is the most frequently-occurring fern.

Bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) and lichens, by Rod Stern

The bryophytes recorded in the site do not provide any significant evidence for establishing “ancient” status for the woodland, but show that it is quite rich biologically, with more than 40 species. Some of the liverworts are of particular interest, including grove earwort and white earwort which are rare south of the Weald. The bryological diversity indicates a low level of atmospheric pollution. The lichens have not been looked at in great detail, and it is believed that the lichenological importances very limited, probably because the habitats are unsuitable.

Trees, by Miles Wilson

The dominant tree is the sweet chestnut, which is mostly present as coppice but there are also some mature trees and saplings. Most of the oaks are the English oak, but there are a few rarer sessile oak present, and some hybrids. There is a regeneration of elms in the southwest corner of the Copse. Hornbeam and spindle, quite rare in the site, are present in the northwest sector. Many of the tree species are non-native, though there are long-standing introductions - common lime and sycamore among them, in addition to sweet chestnut.

A general view of the woodland, by Ann Griffiths

The woodland is generally dominated by sweet chestnut coppice with occasional oak and birch trees. Other tree species are present in low numbers. The ground flora is dominated by bluebells in the south and east of the wood. One or two species more commonly associated with ancient woodland are present in low numbers - these include butchers broom, wood anemone and wood sorrel. Knowledge of the land use history of the area would suggest that most of the site has regenerated, or has been deliberately planted on the earlier open land, at one time managed as a common. Some old oak stump suggest that the wood may have been “plundered” of its oak during World War I or II.

The sweet chestnut has clearly been coppiced in the past - most recently about 1990. Notable features include a small area dominated by oak, and very small patch of heather (ling). The paths and edges generally support a greater range of species - attributable to more light and to disturbance.

Back to List.

Managing the Copse: the past and the future

Brandy Hole Copse today owes much of its form to intentional management. The main woodland area was coppiced to provide fencing posts and the raw material for charcoal, a valuable fuel in the past. Mature oaks may well have been felled and the timber used for ship or boat building. The small survival of ling indicates that when the area was less tree-shaded some of the land could have been used for grazing.

What happens now...

The management plan for the Copse in the first five years of the 21st century sets a number of principle objectives:

· The woods should be maintained as an informal woodland area rather than as an urban park.

· The management must enhance and protect the biodiversity of the flora and fauna.

· The archaeological site should be protected from further damage.

· There is a need to balance the requirements of different users - informal walkers, active youngsters, environmental students, etc.

· Community involvement in the Copse and its management should be increased and efforts made to broaden understanding of the area and to encourage its use in educational programmes.

· A timetabled programme of management and community activities should be introduced, ensuring the best use of limited resources.

A major risk identified in the management plan is increased soil erosion along the entrenchments bank. To avoid this, the intention is to maintain existing undergrowth, including holly, to remove self-seeded saplings and to plant new native shrub barriers where gaps exist. The large trees topping the bank need to be monitored and action taken to stop them becoming too tall, toppling over and damaging the bank.

Positive ways of improving as well as maintaining the biodiversity of the Copse have been suggested by Chichester Natural History Society. Continuing coppicing is crucial, and opening up the area to more light would be a considerable advantage - this could be done by widening some pathways through the coppice, now largely overtopped by tree growth, or creating permanent glades. The benefit of coppicing is that there is regular cutting of different adjacent areas to provide a wide range of ages of regrowth which can support many insects, not just butterflies. The coppicing should be on a regular cycle over 10 or 15 years. Such more open areas would be invaluable in encouraging a greater overall range of plants, which would introduce more seed and berries as well as attracting more invertebrates, thus providing additional food for birds.

Other than for safety reasons, mature trees should not be felled, and more new oaks in particular should be planted to ensure mature woodland for the future. Dead standing timber should be left, and cut or fallen wood allow to decay naturally where it lies, to provide habitat for grubs and insects - the endangered stag beetle among them- and thus add to the food supply essential for bats and birds.

For birds the ponds are a crucial resource for drinking and bathing - birds need to drink daily and wash their feathers to maintain flight and insulation properties. For bats, the ponds are a vital feeding ground. It is therefore essential that these areas of water need to be kept open and unpolluted. More nest boxes would help to increase the bird and bat population.

Continual recording of the Copse flora and fauna will allow the effects of management to be monitored, will help guide future management and will increase the knowledge and understanding of the site which though small contributes considerably to the overall biodiversity of the Chichester area.

With these recommendations to work from, Brandy Hole Copse Conservation Group hopes to ensure the Copse survives and flourishes through the new millennium.

Back to List.

THANK YOU, EVERYONE:

Brandy Hole Copse Conservation Group would like to thank the following organisations which have supported its work, notably:

British Trust for Conservation Volunteers, Chichester City Council, Chichester District Council, Portsmouth Water plc, Royal Military Police, West Sussex County Council, Youth Outset Action/Bishop Luffa School.

Many individuals have also contributed, too many to mention here, but without the efforts of Jim Ayling and Hugh and Henrietta Wingfield-Hayes the Copse as it is today would not exist.

Published by Brandy Hole Copse Conservation Group 2001.

Editing and production: Liz Sagues. Printed by Download Reprographics Limited.

The library edition includes the following on a slip of paper stuck into the rear cover:

2002 UPDATE

Legal formalities regarding designation of the Copse as a Local Nature Reserve having been completed, the Chairman of Chichester District Council visited the open day on 18 May 2002 and accepted a plaque from Jenny Bowen of English Nature.

This designation ensures the long-term future of the Copse and enables additional resources to be available for its improvement. A Management Board consisting of all stakeholders has been set up to administer an agreed Management Plan from 2002 to 2007.

Back cover

The back cover of the publication comprises the map pictured below followed by an invitation to support conservation work at the Copse through subscription to what is now the Friends of Brandy Hole Copse and the names, addresses and 'phone numbers of the Secretary (Jim Ayling) and Chairman (John Herniman). The text is partially obscured by blue tape on the Library copy, and it seems inappropriate to reproduce historic contact details here.

Back to List.